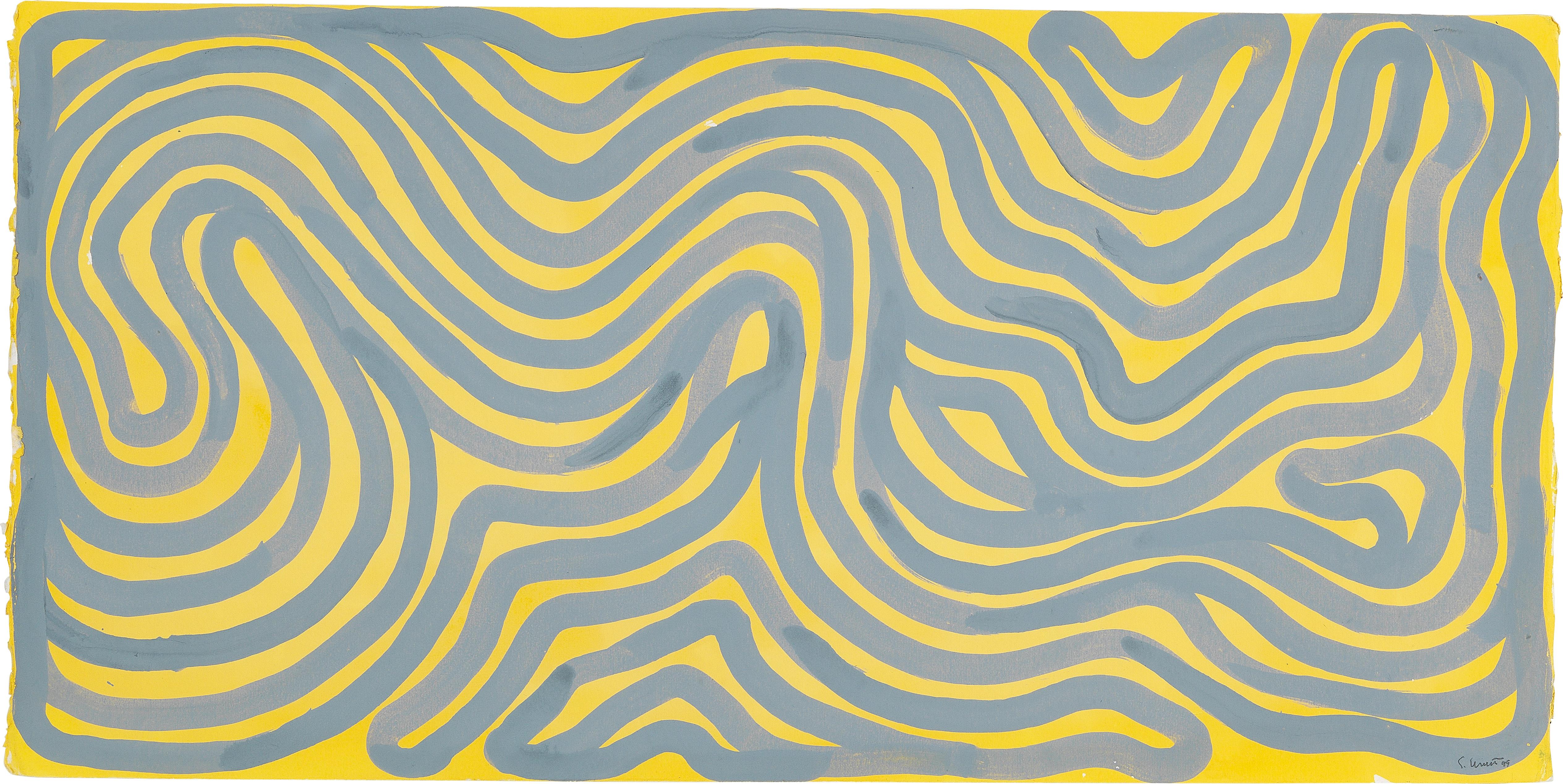

He helped establish Conceptual art and Minimalism of the postwar era. Sol LeWitt’s idea proves to be a dialogue which is still ongoing even more ten years after his departure, timeless proof that the space, as well as the artwork, is rewritten and re-experienced and remains up to date with the observer in the present.Being one of the main figures in the creation of the new aesthetic of the 60’s that was in a contrary to the Abstract Expressionism, Sol LeWitt defined conceptual art with his statement that the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. The optical illusion is incredibly surprising in its simplicity: LeWitt’s grid becomes a way of measuring the room, its decorations and all the other artworks exhibited in that space and, in the end, even the observer. Even more interesting is the experiment made by the Fondazione Carriero in Milan, the curators (which included archistar Rem Koolhas) decided to reproduce the lines of the drawing on a enormous mirror which visually doubles the space in one of the baroque rooms of the building.

In a 2003 exhibition at the Edams Museum for example the scheme was recreated on a window, therefore turning the drawing into a sort of lens capable of measuring the outside world.

The notion of letting the executor to reproduce the artist’s original idea, during the years opened many possibilities for curators and enabled them to transform what was originally intended as a wall drawing into something different. Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #263: A wall divided into 16 equal parts with all one-, two-, three-, four-part combinations of lines in four directions, 1975 / Disegnato la prima volta da Kazuko Miyamoto, Ryo Watanabe, Jo Watanabe, Qui Qui Watanabe, Prima installazione The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1975, Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New Yorkīut the work which could probably be considered the ultimate manifesto of the artist and that most likely includes and summarises LeWitt’s concepts is Wall Drawing #263, a square drawn onto a wall, composed by sixteen smaller squares which, with its lines going in four different directions, seems to explore every possible geometrical scheme as if it was an universal basis. The same mechanisms needs to be applied to works of art: the concept, the idea is what is necessarily coming from the artist but the production can be, and in many cases should be, executed by external operators at any given time and in any given space. Nobody would say, for example, that one of Beethoven’s piano sonatas belongs – intellectually speaking – to the pianist who’s playing it in a concert and not to Beethoven himself and similarly no one would think a great piece of architecture is just the result of the mere hard work of bricklayers. The artist is somebody who is capable of thinking and designing artefacts that will later be physically produced by somebody else without affecting their qualities and originality. If the idea becomes the machine that makes art then the artist becomes more like a composer, or like an architect, a figure which suits LeWitt perfectly due to his great focus on space which is present throughout all his works. This principle was what gave birth to what was later defined as conceptual art, of which Sol LeWitt – as well as other artists such as Carl Andre and Donald Judd – was a pioneer. The idea is the main instrument which enables the creation of art, its visual feedback instead is secondary, possible but not necessary. In 1967 Sol LeWitt (Hartford, 1928 – New York, 2007) publishes his “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art”, in the magazine Artforum, establishing the leadership of the artist’s idea above its execution which could be entrusted to somebody else. Sol LeWitt: shaping the space between art and architecture

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)